The original paper describing TCP/IP was published 50 years ago this May. The technology and networking landscape has changed a lot since then. One of the biggest changes has been the approach to security.

Today’s Internet is so defined by security concerns that it can be difficult to imagine a world where global networking is simple and safe. There are whole conferences dedicated to Internet security and a multi-billion dollar industry committed to foiling the attempts of bad actors. But if we look far enough back, the first iterations of the Internet were built on trust.

In the beginning, every device on the Internet could talk to every other Internet-connected device. Most organizations were primarily interested in mutual access to resources. College campuses and research labs shared specialized instruments and data sets. The postal service and other agencies created international communications channels. Put another way, the Internet was developed and used by a mutually-known and trusted community.

That trust created a beautiful thing. Communities of known good actors could easily access shared resources and direct peer to peer connections made the flow of data seamless. Innovative new tools and applications proliferated, often without any central coordination or planning.

In the current environment where “zero trust” is the ultimate goal, those long-ago days may seem rose-tinted and impossible to replicate. But ZeroTier was founded to “unbreak the Internet”, and we believe that global organizations can have the benefits of a high-trust Internet, without sacrificing security.

Let’s take a quick look back at the history of the Internet and some “vintage” approaches to connection. Then we can talk about how new technologies are helping to rebuild trust in the modern era.

One Internet

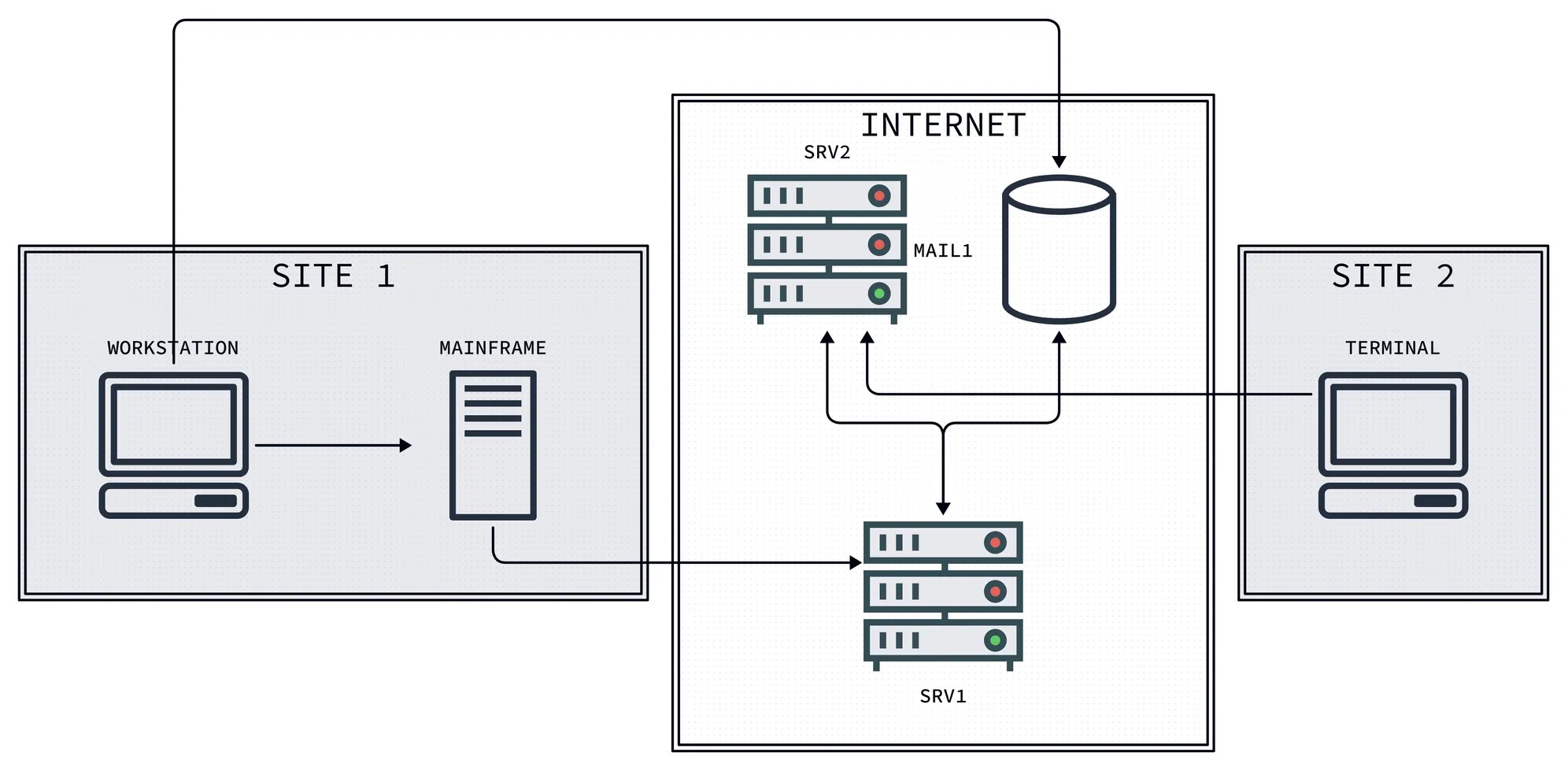

Early in the Internet’s history, the primary (if not only) reason for connecting your local computing resources to the Internet was to allow people outside of your organization to access them. With that primary objective, the community built simple tools and protocols like DNS, telnet, FTP, and the early Web, which focused on ease of implementation and compatibility.

Internal access was provided by local networks and physical access. There were few provisions for security, beyond basic username + password authentication (usually in plaintext, and so vulnerable to interception by 3rd parties).

Network addressing was based on known allocations of public IPv4 space, and operators of any Internet-connected device could easily run services reachable by any other site.

Building Walls

By the late 90s, the popularity of email and the World Wide Web drove demand for Internet services beyond academic and government applications. Unfortunately, moving business online created incentives for bad actors to exploit any weak links they could find in publicly-reachable networks. This forced previously trust-oriented operators to harden their environments.

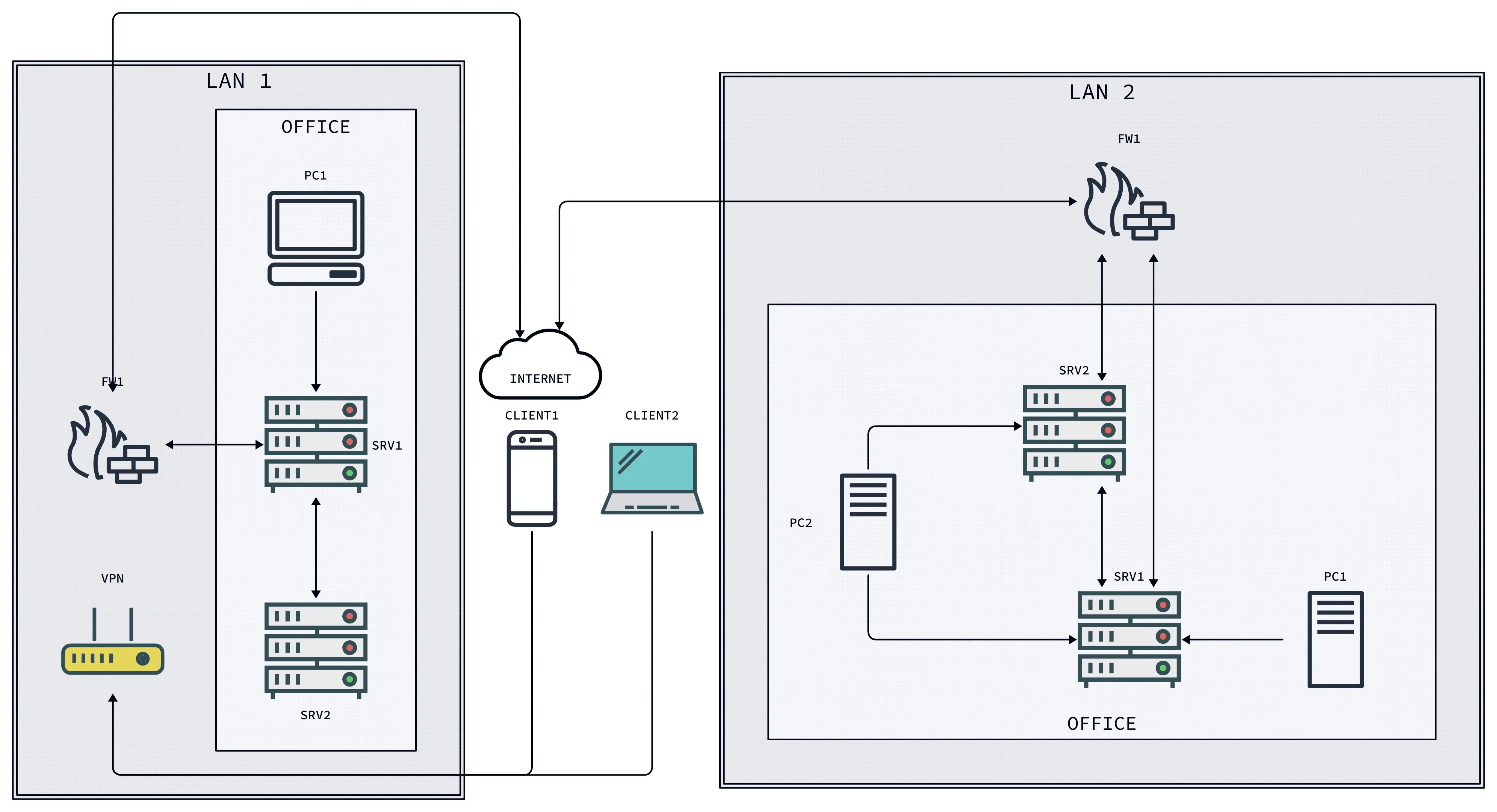

We moved from classic plaintext protocols to encrypted, authenticated ones. Network addresses were increasingly allocated from private pools, with dedicated gateways and firewalls deployed at each organization’s network perimeter to inspect and selectively move traffic into and out of their systems.

Maintaining cross-site access required careful balancing of public visibility and internal access rules. As a result, we developed standard architectural elements like DMZs, VPNs, and proxies to ensure only chosen access patterns were allowed.

Increasing Complexity

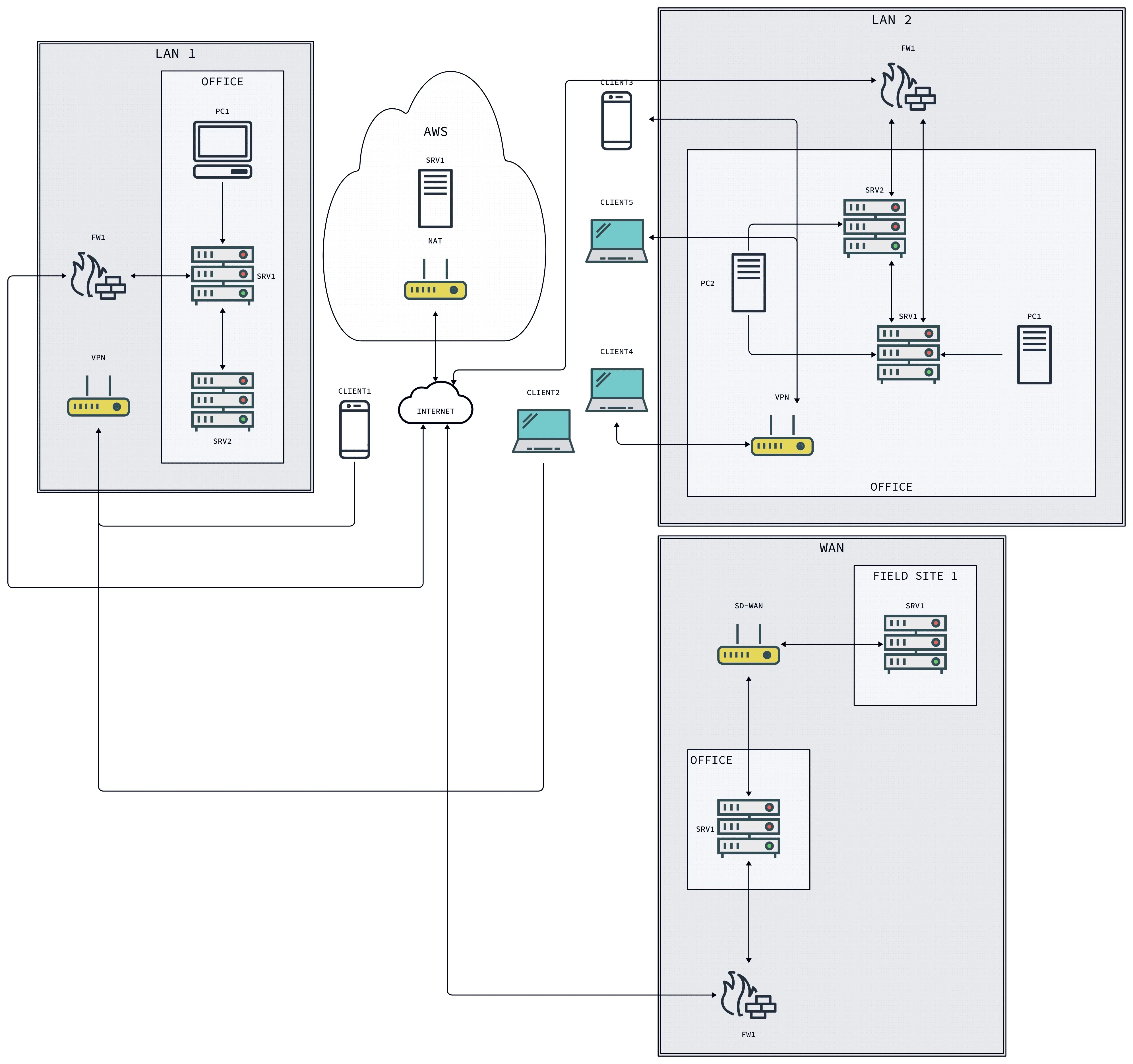

More recently, with the rise of cloud computing, remote work, mobile broadband, and the addition of Internet connectivity to every electronic device capable of powering a small radio, the scale and diversity of network architecture has exploded. It’s no longer reasonable to assume that your employees, end users, or partner organizations will share a high level of trust or use the same network infrastructure.

Today we depend on immediate access to resources across people, organizations, and platforms. As network engineers and IT experts we’ve developed a broad set of tools to serve that need: Zero Trust networks, service meshes, virtual private clouds, and (more recently) private edge 5G.

Deploying and managing those systems requires a great deal of expertise and ongoing investment, usually stitching together multiple platforms and vendors’ offerings.

The Return of Trust

All of this emergent complexity has made the original use cases of the Internet dramatically harder to support. Direct, ad-hoc sharing of services and information now often requires coordination of multiple identity and cloud providers, mapping of different last-mile network addressing and bandwidth constraints, and centralized infrastructure to coordinate across all of those elements.

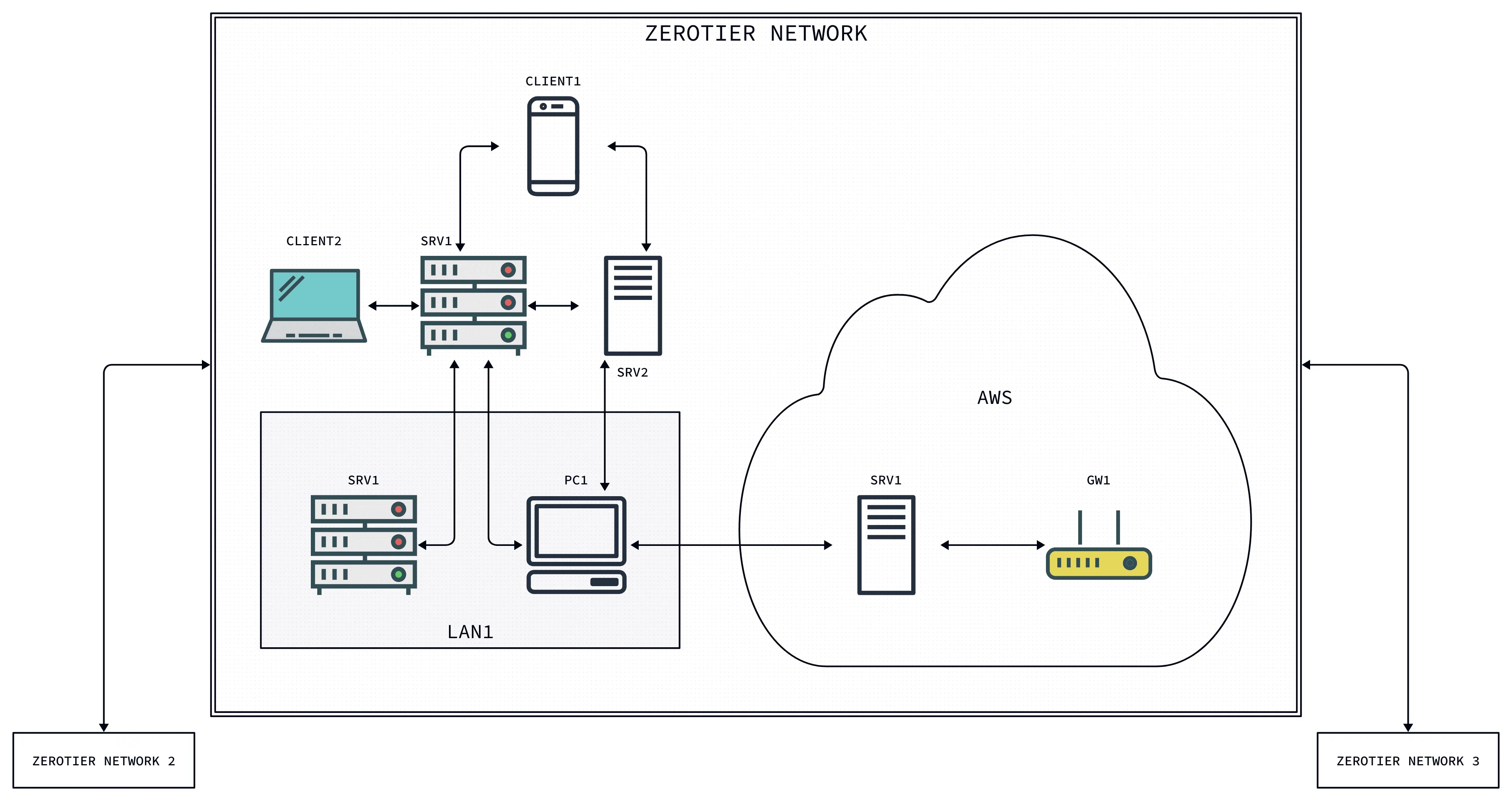

However, there’s a simpler model being supported by a new crop of tools including WireGuard, ZeroTier, and other modern peer-to-peer platforms. Using these overlay network protocols, you can create as many small, private Internets as you need to directly connect trusted peers and devices no matter how or where they’re connected.

These P2P-connected endpoints can run web servers, databases, and services, while easily sharing them with each other. Membership is determined based on unique cryptographic identities for devices and users, rather than physical location or Internet provider. Critical data stays within your network instead of being passed through interminable network appliances and providers.

All of these improvements allow for enterprises to be more nimble and responsive in deploying new services while maintaining and even improving their security posture. By requiring fewer intermediaries, P2P network designs can reduce the surface area and complexity of critical applications, reducing the likelihood and scope of security incidents.

The Future

As we look back at 50 years of Internet history, many of the core ideas that got us here are still valid. And the core value of connection is increasing. The challenge we need to overcome as we move forward is one of simplification. Ultimately, adding layers of complexity to solve security problems is unsustainable and a “zero trust” environment may be impossible to achieve. But if we can learn from the vision of the early Internet, we can find new ways to return to the spirit of trust that made networking possible.